Disparities That Affect Online Learning

Change seems to be the theme of the year, and we – as students – are certainly no exception. Instead of attending classes in-person, students started this year learning remotely, through applications such as Zoom. Though the additional freedom that comes with remote learning has it’s benefits, this method of teaching does come with its downsides – notably, when a student has an unreliable internet connection; or, when he or she does not have a connection at all.

As if high school wasn’t frantic enough already, online school has been able to transform consistent attendance into a luxury, for some. Remote learning requires a stable internet connection – something not every family can afford, as internet is not cheap, by any means. Lower income families may not have internet simply due to the fact that they must prioritize more vital necessities; which, themselves, aren’t cheap – things such as food, shelter, heat, etc. Furthermore, remote learning has amplified the disparity in productivity that socio-economic inequalities can create within a learning environment.

Though it’s no reason to diminish the nation-wide issue, we – as a school – do not seem to suffer from these issues, to the fullest extent. Being a school lucky enough to be able to distribute Chromebooks to every student, Mountainside doesn’t see many students suffering from the switch to online learning. Out of a poll of 235 MHS students, 100% of participants stated they had access to internet. At its worst, some MHS students reported losing WiFi during class, but even such a problem has simple solutions.

“I don’t have any problems, but I occasionally have such bad wifi that I use my hotspot,” said Micah Marrs – a Sophomore at Mountainside.

“I know people with shaky internet and all of that. You just wait for it to work or skip the classwork.” – a student who wished to remain anonymous

Remote learning can make it harder for students to stay on the same page as the teacher. Shaky internet, at times, can lead to a student being removed from a Zoom meeting. The pace of the lesson tends to suffer as a result, since a single teacher usually can’t manage both teaching and monitoring the status of each student. Even if a student is re-admitted into the meeting, there is a good chance they missed a significant portion of the lesson. This leads to knowledge gaps which only worsens the pace of either the class as a whole, or the re-admitted individual’s workflow. Either the teacher must stop and explain what the student missed – at the cost of the rest of the class’ time – or they must do their best to catch the student up through individual messages, during a work time or after class, which still means that student is behind the rest.

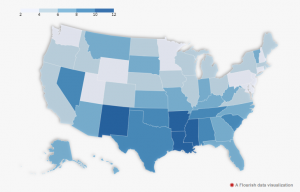

Though Mountainside doesn’t see the issue at its worst, this does not mean that the issue is non-existent, or even mitigated, just because the problem isn’t seen at MHS. The Associated Press has provided data for 2019, which has shown that, nationwide, 6.27% of households do not have internet and 16.24% do not have a computer.

Many students outside of the Beaverton area are not as fortunate and, consequently, do not have access to all the amenities that we do – causing them to be stranded in this new landscape of remote learning.

Even when technical difficulties are removed from the equation, the inconveniences that come with the separation of the student and teacher remain. If a student has a question, outside of class, their options are to email their teacher or wait until their next meeting. Rather than just being able to walk up to a teacher and ask your question face-to-face, you have to wait for an email back, which, of course, is nowhere near as efficient. It’s now up to the parents to provide answers, if the teachers are unable to respond. Even if a child is fortunate enough to be side-by-side with a parent throughout the online school year, reliance on an adult isn’t a guarantee of success, especially in families where parents struggle with understanding the curriculum themselves.

Meaning, it’s entirely possible that education inequalities can span over generations. Remote learning’s separation of the student from the physical classroom – and consequential limiting of student-teacher communication – only helps sustain that generational loop. Those who have been dealt bad cards in life don’t deserve to fall behind or have additional barriers placed in front of them.

Speaking of perpetuation, we feel it should be discussed how the effect of these new learning conditions may follow students post-high school. Should we be worried that the negative effects of remote learning could span well past the pandemic? If certain students are placed at a greater disadvantage in lower grades, as of now, how will they fare in, let’s say, in high school? Will there be large knowledge deficits? If there are, how will it affect their chances of being accepted into colleges? Even if they choose not to attend college, wouldn’t that still create a less-educated workforce?

If any of the above were to occur, what kind of future is the world looking at? An under-educated generation of students being released into a broken world can’t be a good thing for anyone. While education is typically the responsibility of a government, should the private sector – which regulates the systems needed to run online school – also step in to help? A transitioning American government could always use the help, and the private sector cannot afford it’s future employees to be under-educated. It is just a thought, as we – alone – can’t offer a full solution.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Mountainside High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Originally, Benjamin Rejab had not much interest in Journalism. He signed up because he felt he was a strong writer, ultimately finding himself really...

Cole Bennett is a Mountainside student who writes for The Peak. He enjoys listening to music and skating, and he is interested in trying track and field...

Noah Wymbs is a senior in the Op-Ed department. He joined The Peak with an aim to look critically at how things work at Mountainside and share his opinions...