Behind The Sparkle

Kron4: ‘I hate this sport’ , NBC Sports: ‘On Her Turf’ , Parade.com: Who Is Yulia Lipnitskaya?’

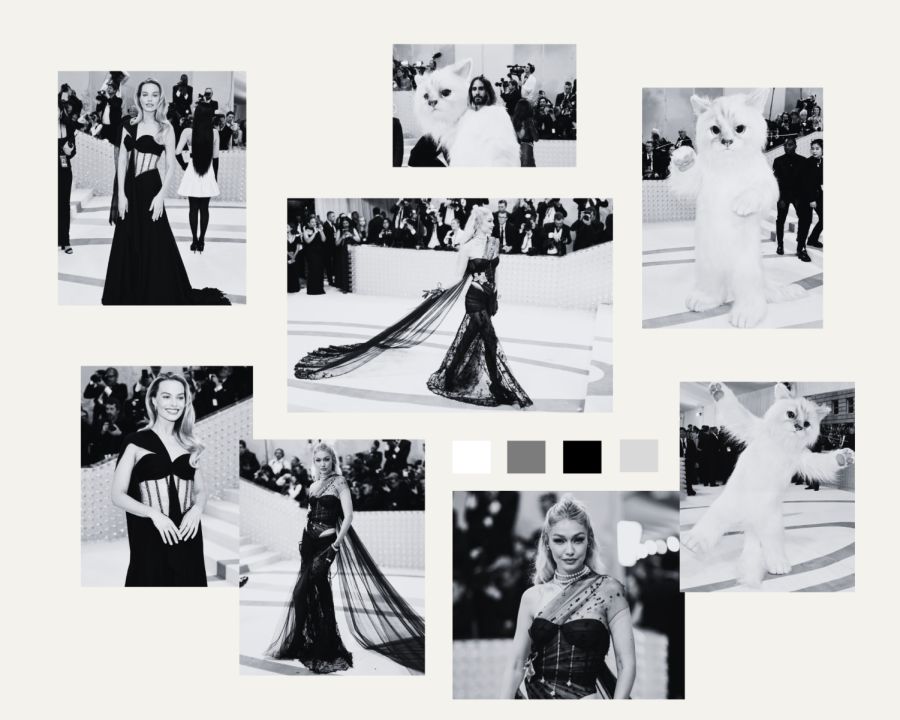

Yulia Lipnitskaya during her short program in the 2014 Sochi Olympic Games, Alexandra Trusova crying after receiving second place at the 2022 Winter Olympics, Kamila Valieva reacting after falling during the 2022 Winter Olympics

December 7, 2022

Everyone has something they’re good at. Whether it’s art, singing, or playing an instrument, it’s their talents that make up a significant part of who they are and how others view them. For some people, they may want to prove themselves and see how far it takes them. A little competition can be a good thing, as it toughens one’s skin and forces people to face and overcome obstacles. But there’s one thing that isn’t talked about enough: At what point can competition become unhealthy?

Figure skating was first introduced in the 1908 Summer Olympic Games, performances consisting of technical spins, jumps (the Axel, the Lutz, the Salchow, etc.), and footwork. Figure skating takes years upon years of practice to master. The beauty and grace of the sport hasn’t failed to grab attention. Viewers admire the skaters’ attire, intricately pieced and sparkling with sequins, the smooth, effortless movements they execute, and the way they seem to float across the ice.

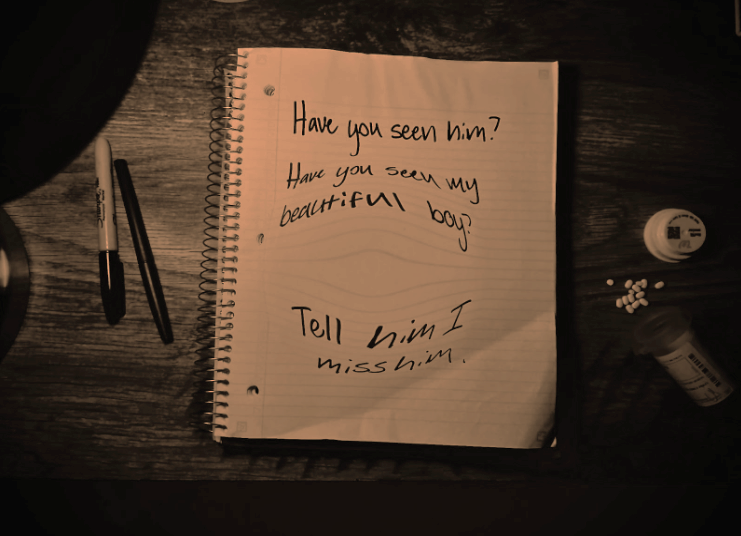

The life of professional skaters can come with a desire that steals the joy of skating itself. For instance, winning the Olympics brings recognition, fame, and money, which fuels the fire for competition. This can make coaches push young skaters to the point where they abuse them physically, mentally, and emotionally.

Kamila Valieva is a Russian figure skater. Prior to the 2022 Winter Olympic Games, she was caught in a doping scandal after she tested positive for trimetazidine, a banned heart drug. Trimetazidine can improve physical efficiency and endurance. Valieva claimed it was a mix-up with her grandfather’s heart medication. While it’s still uncertain if she was intentionally doped, there’s no doubt about the immense pressure that comes with figure skating and the belief that taking this drug is needed to enhance athletic performances.

Many students of Russian figure skating coach, Eteri Tutberidze, have ended their skating career early because of her abusive practices and coaching. From weighing her skaters with harsh expectations to making them run through programs for several hours a day, Tutberidze’s former students were forced to leave with both physical and emotional duress.

One of the students, Yulia Lipnitskaya, retired at the age of nineteen due to the chronic anorexia she developed because of Tutberidze’s strict fixation with weight. Besides Valieva’s doping scandal, the 2022 Winter Olympics sparked an angry breakdown from Alexandra Trusova, another former student of Tutberidze. After placing second, she cried that she hated the sport.

Eight months later, she split from Tutberidze’s group and Svetlana Sokolovskaya became her new coach. During Trusova’s tearful scene, gold medalist Anna Shcherbakova sat alone, blank-faced, celebrating out of the picture. All of this goes to show how damaging Tutberidze’s coaching methods are, shattering the futures of young skaters and damaging their health physically and mentally.

The burden on young Russian skaters’ shoulders is one not to be ignored. Their capability and potential become crushed with unrealistic goals, whether the goals are from themselves or their coaches. Coaches should put their skaters’ health first instead of forcing them to chase gold. Competition should be a way to challenge oneself in a healthy manner.

Junior Sophia Wiesmann took to figure skating at eight years old after being inspired by watching Disney on Ice. Through a figure skating group her rink had, ‘‘Rising Stars’’, she participated in her first competition. Around a year later, she performed another competition with a private coach.

Although competing was something Wiesmann enjoyed in the beginning, she suddenly developed stage fright during the third grade. ‘‘It made me feel really nervous during competitions and right before I went on the ice for a couple of years,’’ she said. By the time sixth grade rolled around, however, her stage fright had become almost nonexistent.

COVID-19 made a significant impact in Wiesmann’s skating. She was fourteen when rinks shut down, and scheduling to skate during the pandemic was difficult. Before the pandemic, she had been skating five to six times a week, three days a week skating before school. Once everything shut down, Wiesmann and her mom realized how packed her schedule was, and how exhausting it was to do so much at once.

As for after the pandemic, getting back on track wasn’t easy. From transportation and schedules, clubs, theater, and schoolwork, it was hard to balance it all. For these reasons, Wiesmann came to the decision not to take figure skating as seriously as she used to. ‘‘I think if I were still skating as much as I did back then, I would definitely be experiencing a lot of burnout,’’ she said.

Now, Wiesmann has lessons with her coach once a week, focusing on moves, jumps, and spins. ‘‘Currently, I’m not working towards doing a competition anytime soon. I would definitely love to do another one in the future; it just comes down to if it’s in the area, and if I have enough time to practice for it.’’

Tyler Douglas, sophomore, was fascinated by the figure skaters who would practice at the same time as their older brother’s hockey practices. This led to them figure skating at the age of eight.

A mix of physical and emotional burnout resulted in them quitting at thirteen years old. There were times they would skate on an injured foot or leg, and developed horrible arch pain from their skates, something they still live with.

Although they were able to keep it more laid-back when they had injuries, they still had to be at the rink for the same amount of time almost every day. ‘‘I’d also make myself go on days where I was upset and practically skating in my own tears,’’ Douglas said.

Spending time with others outside of the sport helped them with the emotional side of burnout. ‘‘That social aspect was one of the reasons I was able to go on for so long.’’ Douglas hasn’t skated since they quit, but is definitely open to it.

The drive for competition and winning can be blinding. It’s important to realize when burnout is around the corner. At the end of the day, ultimate satisfaction comes with self-fulfillment rather than the validation of others.